Time, Memory and the Art of Spilling Milk

On reading Karl Ove Knausgaard's Min Kamp (My Struggle)

Before an answer, came the right question. For one could never stumble upon the truth if there is no life force driving one to it. As Knausgaard puts it, literature is reaching the unknown through the known. The question for literature is how to build a universal known to reach the specific unknown and then translating this specific unknown into the universal known. It is this knowledge generating process, that begins with a question, which decides the life force of the whole endeavor. Hence, when I finished reading Min Kamp (My Struggle) by Karl Ove Knausgaard, the central question for me was how I translate why reading Knausgaard is essential, into a language which is both mine, and can be borrowed by a reader to form their own world.

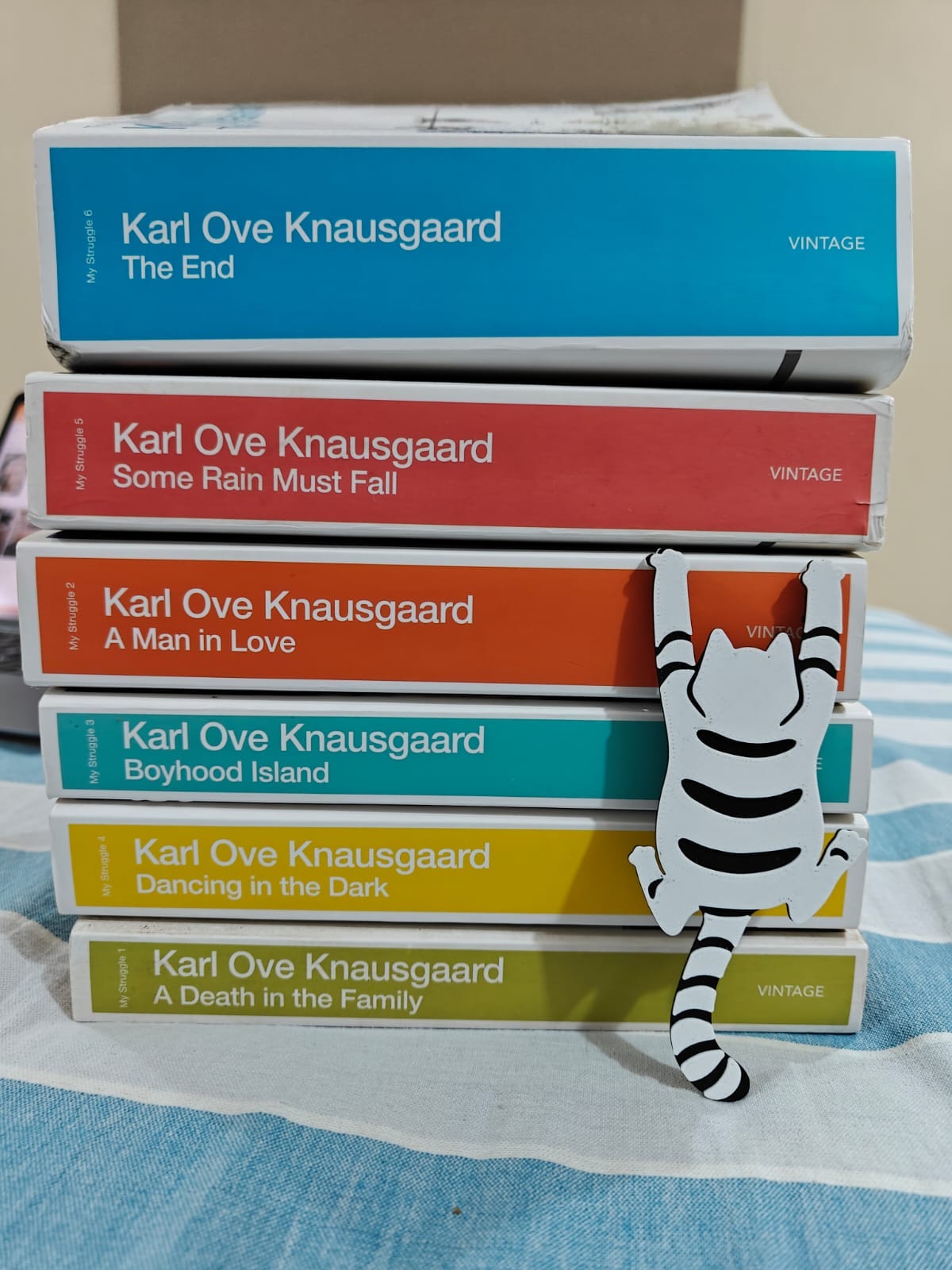

Th further questions, it gave birth to were: What is an essential reading? Why could I not live through my life, not having read about the life of a Norwegian writer? Could beauty be the central tenet to calling something essential? Who is it beautiful and essential for? Is going through 3600 pages across six books, reading about how a man strolls around parks with his kids, or 60 pages of how he goes to the bathroom, really worth it?

The short answer is mostly no. I am not sure of which question, but if the short answer is what you were looking for, it is mostly no and it’s okay if you drop off here. The slightly longer answer is that you could live through your life not having read Knausgaard, and it is not essential in the same way, as reading Proust is not essential. Both of which, if you read, there are chances that it could change your life the way it did mine, which is why I write about it as if it’s essential. It is essential in the same way most art is essential, that it makes you feel less alone, that it opens your mind to possibilities you could not have imagined, that it builds a collective entity, a we with the world that transcends limitations of space and time.

Hence, we start with the fundamental question: What is Knausgaard trying to achieve with this experiment, and why is this an experiment unparalleled to anything written before?

At the surface, Knausgaard is attempting to reconstruct his life story. He does it in incredible detail. A micro-realist fantasy unfolds as every place, every touch, every scent, comes forth and builds a picture for us. He is attempting to hold nothing back, to write everything as it happened, to empty himself of a lack that the death of his father has opened. However, the more you read it, you realize that it is more than that. There is something latent happening beneath the surface. You are drawn into the story because it is our story too. But how could a story of a Norwegian writer, whose life mostly centered around Norway and Sweden be our story? How could the intimate details ranging from how the trees swayed outside the window, to the color of the toothbrush, make us think of our own lives?

Here is where Knausgaard reveals the paradox of literature and resolves it too. The paradox is as follows: Great literature aims for the uniqueness of the I, that is, each great writer has a distinctive voice. It is one of the few places where repetition is penalized, to the point where using beautiful twice in a sentence sounds odd to the reader’s ears, so the second beautiful needs to be replaced with a synonym, and where plagiarism is considered a mortal sin. However, all great literature also aims at universality, in a shared language that can only convey the individual ideas when they are shared ideas. The reader needs to have a conception of what the author is attempting to convey, or else all comprehension is lost. This opens a chasm between the opposing purposes of literature, where it is both local and social. For what voice could be more individual and distinctive than the one which only I can understand? But I need to cross over to the we, and the we can be as limited as me and one reader, to fulfill the purpose of communication. However, the moment it is opened to the we, it is not purely local. It exists in the social sphere. It borrows ideas and concepts from the social, for it is only through those ideas that I can convey the particular. But the particular it is trying to convey is emergent. It does not exist in the social I, or the identity as one knows themselves, but an attempt to wrest out something deep hidden inside which transcends the space between identity and reality. This space between identity and reality is the journey both the reader and writer are on, because essentially both are trying to understand something about themselves through literature. The writer is doing it by going within, by using a shared language where it is not the language but the lexical structure which distinguishes them. It is how one word comes after another, how the light falls on a tiny spot through the window, and how the slanted mirror reflects your face to have you glimpse at your reflection as you look at yourself writing a page, and in that moment you do not recognize the person staring back at you, for you are untethered. You are both within the language and the language. In the language, the I is as important as the slanting mirror, or the light that enters through the window. It is not just the writer’s I that distinguishes them, but a unique literary mood they can develop through their writing, for if I were to remove Knausgaard’s name from all his books, and read his I, his I could be anyone. Yet, what remains is this intangible voice. Not the ideas or the concepts, for they are endlessly repeated, but the way those ideas and concepts seem to come from a reality, which pulls the reader into an alien world from outside.

For here is how Knausgaard resolves the paradox. He understands that within the I of identity, is contained a you or a they, for an identity is a social construct. There does not exist an I, separate from the outside world, and hence every I is implicitly a we. For the I needs a you to become a we. One could understand this movement as the inner intangible being, attempting to wrest its way out through the I of the writer, and the I of the writer searching for a you to be comprehended and understood. It is only through this you, that the inner being of the writer, which is unique and personal, gets its meaning. This meaning, however, is socialized, for we need a common language, common concepts, common images to be understood. Instead of the meaning, the way this meaning is expressed is what distinguishes the uniqueness of the author.

It is through this understanding that he elevates the specificity of his life to a universal experience, for once the reader is rooted into the scene through common motifs, symbols and feelings, then he can elevate the specific to the universal. For it is his awareness of both the local and the social, that he is able to fulfill the Saunders’ dictum, that the key to writing a good story is making a character in enough detail that the reader feels some connection with them, this connection being a reflection of the reader’s you in the character’s I till they form a we, and then everything that happens to the character’s I will seem meaningful to the reader.

However, Knausgaard goes one step further. It is his awareness of this interplay of identities, that he borrows voices. He does it quite self-referentially. He is not plagiarizing. Nor is he parodying. Rather, he is building on it and elevating it further while maintaining his uniqueness. The point of Knausgaard’s magnum opus is not just narrating his life’s story. Rather, Knausgaard is pulling a magic trick — a literary miracle. He calls forth the reader to immerse themselves into the magic. In fact, he details out the intricacies of the magic trick he is pulling off. He holds you by your hand and narrates to you how the miracle is performed. While he reveals the magic, he creates another trick. It’s like being entrapped in Knausgaard’s world, and while the mundane takes place in incredible detail, you have the faint sense of a miracle taking shape. This faint sense of being a part of his world, where there is an unrecognizable beauty contained within the language, within the way things unfold, within the novel’s structure, but it is not metaphysical. It is a cleverly crafted trick, a product of rational choices, which the author doesn’t even try to hide, but rather lets you on to. Like a magic trick, you have the sense that it is leading on to something, that there is a broader point to all of this. The point is hidden in the controversial title of the book series. Min Kamp, the Norwegian translation of Hitler’s Mein Kampf, is a conscious choice, which reveals itself in a dense 400 pages essay, tucked in between the plot of the final book. Since the first book, you sense that Knausgaard borrows the voices and structures from so many authors he has read throughout his life. His long meandering sentences, describing memory in detail, and jumping between time are Proustian. The figure of his tyrannical father looms like a Dostoevsky character. His self-hatred never leaves him and follows him like Ged’s shadow in Le Guinn’s Wizard of Earthsea that he reads at 11. He invokes Dante and structures the journey of him becoming a published author as a journey from Hell to Paradise. He also invokes Hamsun, as he proceeds inwards and uses nature as a tool to show that movement.

All of this is not only done to showcase his skill but are rather hints to what we are moving towards. For it is in the last book, that he reveals the trick. It is in the last book, that the idea of his narrative reality is questioned. How can Knausgaard remember his entire life in so much detail? While he claims that he was drunk to the point of having no memories of his days in Bergen, yet he can remember exactly how each party went, and what he did and how he reached home every night. It reaches his culmination when his uncle challenges his core memory of the death of his father, and claims that he is lying in his book about how it happened. It is then that Knausgaard discusses the subjective representation of reality. That a lie told enough times with a seductive force, and with people who are willing to believe in it, becomes a truth no matter how obvious its lack is. It is then that we begin to notice the parallels between the form, the structure, the emotive force, and the critical insight into the way Knausgaard writes his Min Kamp. It is then that we realize that all this while, the voice we have listening to, is the voice of no one else but — Adolf Hitler.

This is the epochal moment, where Knausgaard is both Adorno and Hitler. The 400-page essay stacked in between the plot, which initially seems misplaced, begins to unravel the whole trick and it still asks us to believe. It still retains its root to reality. It showcases the similarities between a young Hitler and Knausgaard, and attempts to humanize Hitler, to ask courageous and critical questions to the reader, about their own resistance to propaganda. Our own understanding of evil. Of Mein Kampf’s place in the literary canon. He discusses the immorality of his own act, of writing about his life in so much detail, which not just concerns him, but his entire family. There is no voice but his, an Absolute which does not describe but shape reality, and whether the reader in yearning of the Absolute, forgets that reality is relative. The 400-pages so cleverly cuts into so many domains of literary, historical and cultural analysis, while intermeshing with the main plot, and highlighting the trickery of the author that he exposes himself, that it seems he is both the executioner and the executed.

Min Kamp (My Struggle) is an ambitious project. It spans across 3600 pages, so cleverly embodies intertextuality to the point of accommodating such a wide oeuvre of Proust, Dostoevsky, Le Guinn, Dante, Hamsun, Joyce, Adorno and Hitler. It does this without seeming conceited, being extremely readable, retaining its own voice and even if one does not understand the subtler motifs, or the latent trickery, being extremely human and moving as a story of the writer’s life. At the end, as Knausgaard is sitting typing the final pages of his novel, he relishes in the fact that he will never do anything like this ever again to his family, that he is finally done with what started as a reaction to owning his narrative after his father’s death, of owning his life which was always haunted by a shadow. At the end Knausgaard revels in the fact that with the end of this book, he will no longer be a writer, and as a reader, for the final time, despite knowing that you will read and he will write, you exclaim too, that finally you can stop being a reader.

[The ideas are inspired from Karl Ove Knausgaard’s own explanation of how he views literature and reading, and Manny Rayner’s incredible analysis of the intertextuality within Min Kamp]